We realized we had to take matters into our own hands if we wanted to visit the baby. For two months, we had reached out to the state-appointed caseworker to see how to get on the visitation list at the hospital. She said we’d have to obtain permission from Mom, and she wasn’t answering our calls or Facebook messages, her phone number changed numerous times, and it became apparent that we needed the court’s help. We ended up showing up to one of the court hearings and saw Mom for the first time since the birth. We wanted to assure her that we were there because we were concerned about her, and we wanted to visit the baby, and she granted permission. The judge approved it, and had Mom sign a printed agreement so it was official for the hospital and court records.

I don’t know if you have ever visited a NICU, but if you’re looking for a solemn, nearly silent place to count your blessings, it’s a good place to do it. As the imposing steel and metal doors opened in opposite directions, we timidly stepped through the vortex of uncertainty into the amber-lighted, sterile, squeaky, reflective linoleum hallways. We walked slowly, and examined each “then & now” plaque of a tiny human miracle whose parents poured out unquantifiable words of gratitude for what those nurses and doctors had done for their precious everything. Those plaques provided tangible hope for anyone in any bleak situation—not just neonatal.

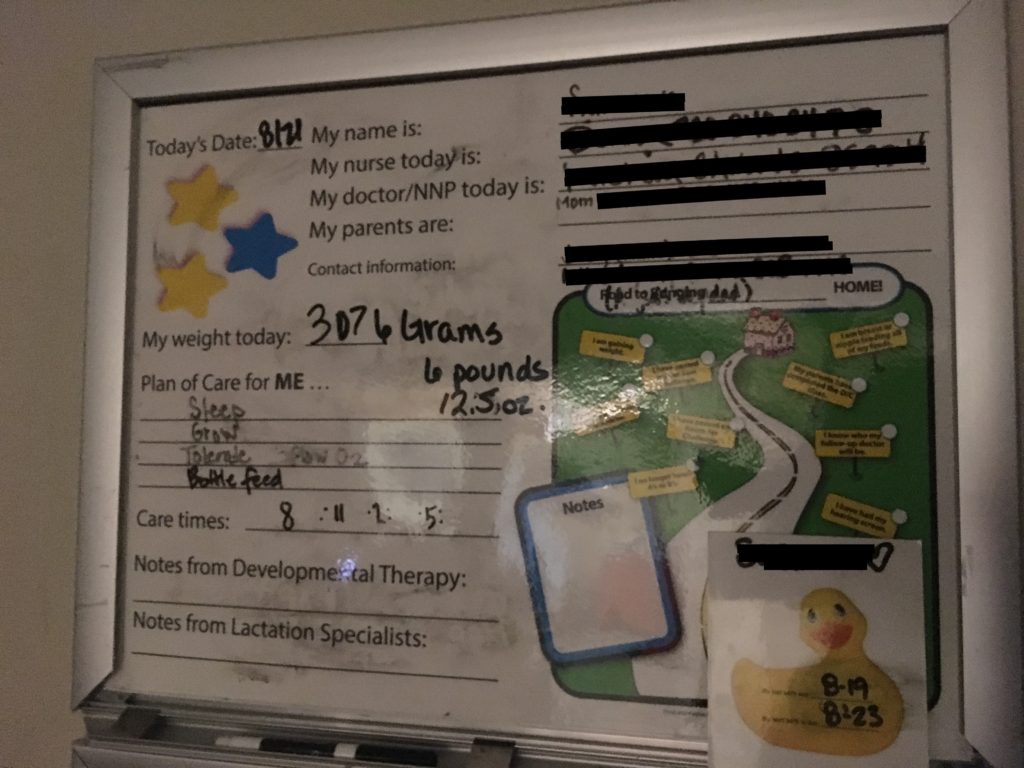

One of the first things you’ll notice in a NICU is how every nurse whom you pass in the hall wears a permanent smile, because they’ve found their vocation. They have an undeniable spring in their step that most people would be so blessed to find in their own walk of life. But, when you enter their world, they need to know you’re dedicated, too, or you’re wasting their time, and every minute to them could mean life or death in a newborn intensive care unit. Such was the case when we met Baby for the first time. I will never forget how peaceful she looked in that transparent plastic “crib.” The plastic sleeve dangled at the foot, with the words, “It’s a girl!” enveloped in measurements and times and incomprehensible birth weights—Baby made her debut at just 1 lb., 9 oz.

We got some guff from the night nurses the first time we showed up in the NICU. We experienced side-eye like never before. They weren’t about to parlay any baby care knowledge on someone who was only going to show up once or twice. But, once they started to see our faces every single day, and balanced by our close friends on the days we couldn’t be there, they laid down their arms, and even smiled once in awhile.

Her head was turned slightly to her left, and her perfect tiny ear and disproportionately swollen cheek from the diuretics were the only skin I could see as I peeked over the crest of her tightly swaddled little body, her muslin-draped shoulder—all so very tiny. She weighed just about 5 pounds, that day—three pounds more than the day she was born, and still an entire two pounds lighter than my older girl on her birthday. We just stood there, mouths agape, until a flutter of movement caught our eye. It was the night shift nurse in the corner who was feeding Baby’s bay-mate. Nurse Shawna was her name, and she was giving us the silent side-eye, and rightfully so. Where had we been, after all, when this child fought to exist for two-and-a-half months with no one consistently there to help her along the way? Were we just there for the show, or were we in it to win it? She wasn’t about to make friends until she knew.

Guardian angels wear scrubs, sometimes.

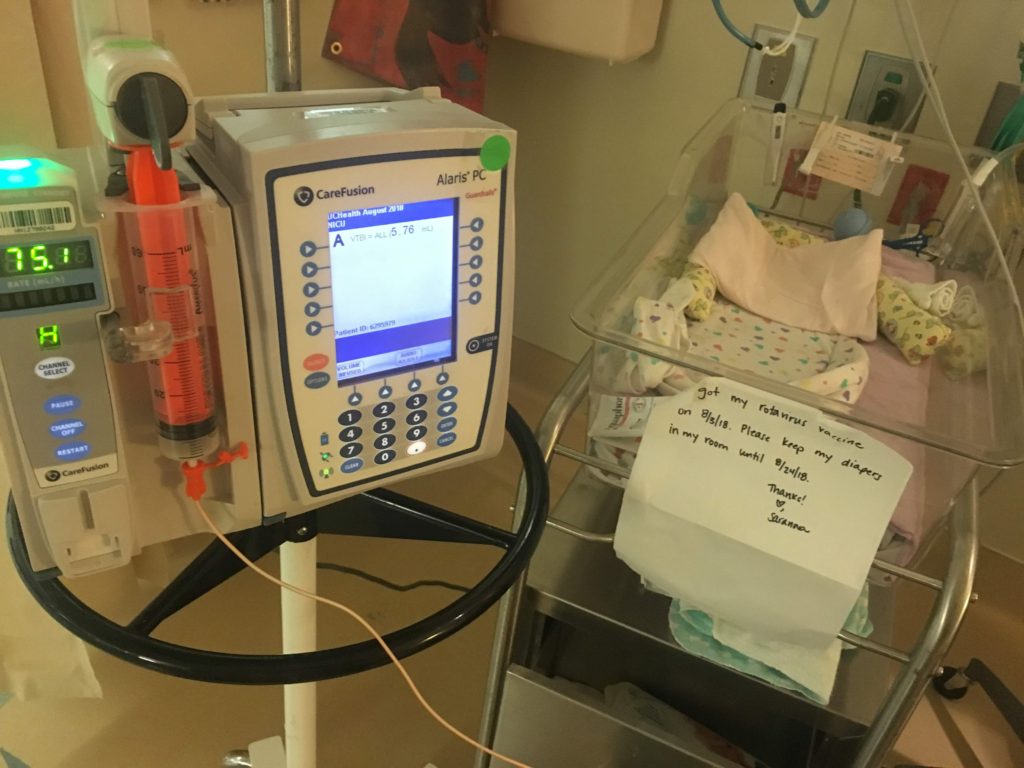

We started coming every day, beginning the day before my daughter’s 5th birthday. Paige had always asked for a little sister, though we never thought in a million years this might be the way we’d fulfill her dream. After the first two weeks, Shawna and the other primary nurses who had initially shuttled Baby in from the helipad, began to take us under their wing. With each visit, we learned a little more—and realized how little we knew to begin with. We memorized a special combination of two formulas. We learned how to feed her on her side, completely, with the thickened formula, to avoid choking and bradycardic episodes, because thicker liquid is easier to swallow than thinner liquids. We learned how to watch for severe chest retractions, labored breathing, blue lips, moddled skin, and how to adjust the teensy nasal cannula that provided her with just the right whisper of oxygen to keep her O2 levels where they needed to be. We learned how to feed the oxygen tube out the bottom of her fancy jammies that zipped from the top down, so as to avoid the tubes getting yanked or too close to her neck as she slept.

Side note: the quickest way to identify a preemie caretaker noob is when they try to take a onesie off over the baby’s head, instead of pulling downward (tubes and wires by the toes, not the nose, silly). Guilty as charged!

We fluctuated between sheer terror and peace—daily—knowing the experts were right there if we needed them, but holy cow, how would we ever do this without them, if we were the ones who brought her home?

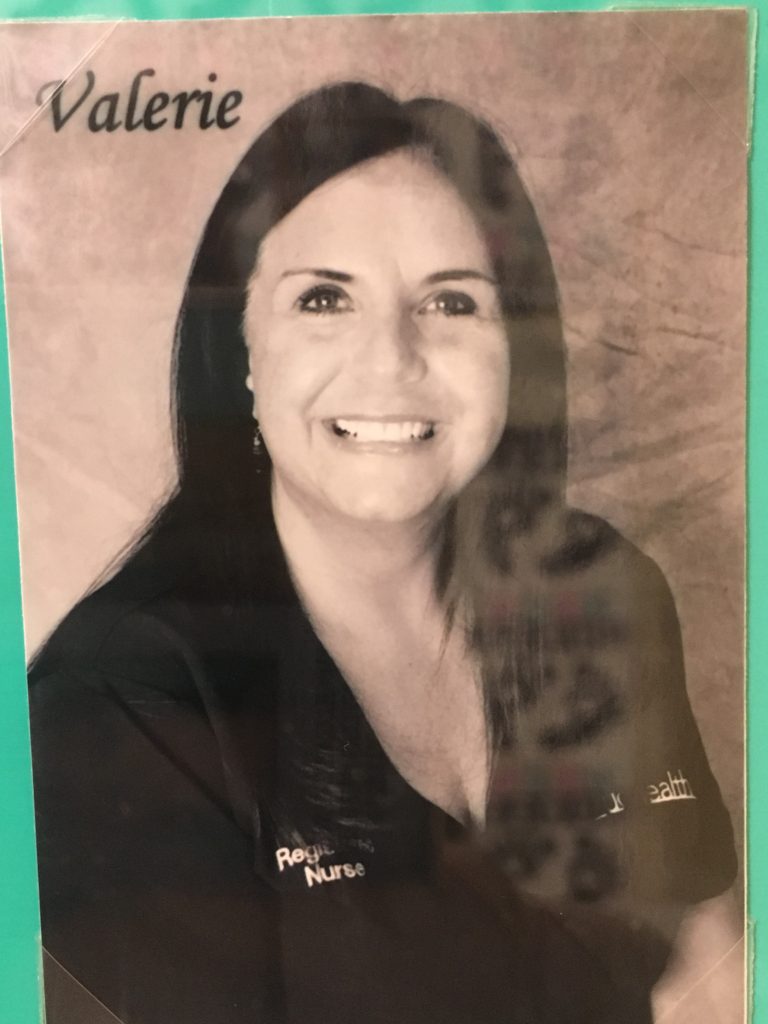

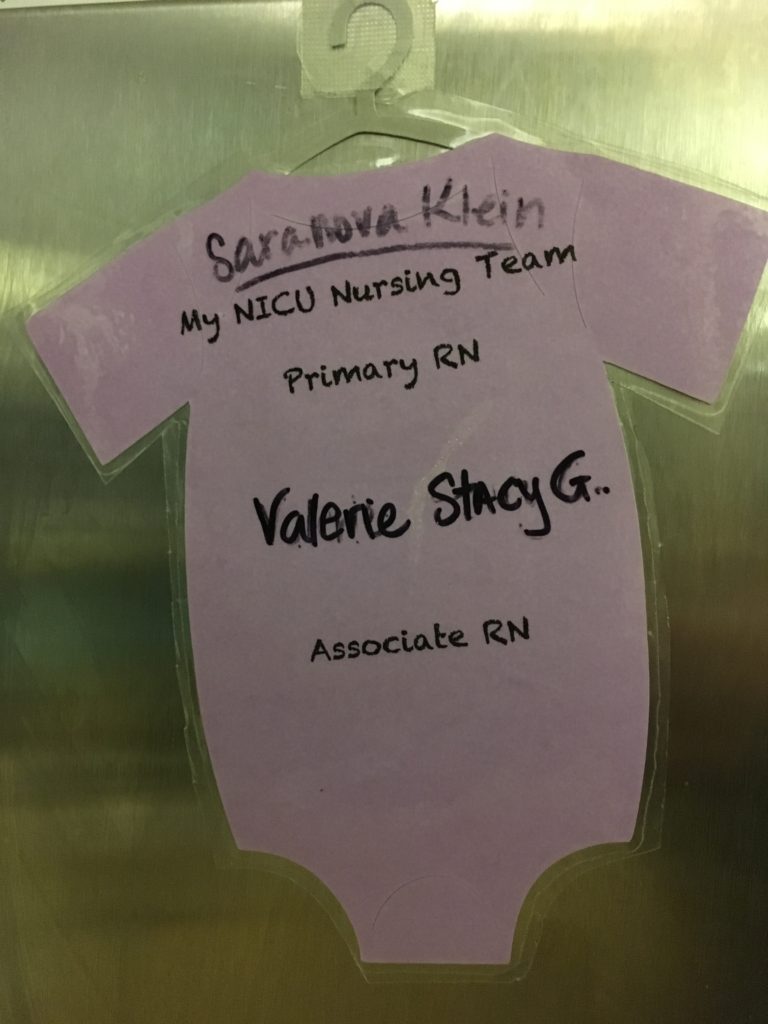

Lemme Tell Ya ‘Bout Val

Val was one of Baby’s primary nurses during her entire tenure at the hospital, and remembers her birth weight till this day, if you ask her. One night, I was there for a late feeding, and she sat down to say, “Are you taking her home?” The very question was one I had avoided, because I didn’t quite know how to respond, and it was the first time they had asked so directly. I paused for a long time. When I finally spoke, I said there were so many uncertainties about her health, with the exposure to drugs, and we had a child who was used to our undivided attention for five years, and what if she feels neglected, and our friends (who had been visiting her on our off days) want her, too, and would we be able to provide her with the care she truly needs?

I showed my hand perhaps all too quickly that day, because she said something to the effect of, “You don’t need to worry. We wouldn’t be sending her home if we didn’t think she’d be perfectly fine. I have been praying for her since she got here, and I think you will be just fine. And regarding her health? Studies show that a stable home can be night and day for children like her. You have the ability to give her a stable home, and the very fact that you’re aware of this shows me you know what she needs.” I told her of my own struggles with fertility, and how I felt this might be God’s way of telling me, “Hold up! I have other ideas for you.” And we both cried with the Baby in the NICU bay, that day,

I cried all the way home, because I knew we had to have her.

I guess you could say, the rest is history. But, there were myriad steps in between. We went to New York City on a family trip in September of 2018 that was planned before any of this came to fruition. While we were gone, Baby slipped deep into a bradycardic episode, and the NICU staff had to stimulate her to bring her back. We called to check in, and that was the first time I was hit with a major twinge of, “We need to be there for her, no matter what.” We never would have dreamt that that would become a reality only eight days after we landed back in Denver.

Before we even adjusted back to Colorado time, and a very short series of days began with no bradycardic “events,” we found ourselves in a flurry of oxygen tanks and “tender grips” stickers (nothing about them was tender), and teensy nasal cannula trainings by a guy who barely spoke English, and flung a heavy black shoulder tank satchel at us, and said “Good luck,” in some Russian-sounding accent that resembled Liam Neeson’s nemesis in Taken. Then, we were shuttled into a conference room where I can only imagine the smartest of smarties assemble—which further emphasized my feelings of unworthiness. In that room, they unleashed a flash flood of “How to Take Care of a Micro Preemie Upon Discharge 101,” including carseat safety, CPR and breathing testing, a “how hot is too hot” bath meter credit card thing, and a tiny, “March of Dimes” teddy bear. “It’s a cinch!” she said. “This is the dial that does this. Leave it on 1/8 of a liter, and shut it off, but don’t twist this too hard, or let it tip over. Store it on its side, NEVER vertically, because if it tips, it’ll break off the adapter and shoot across your living room like a rocket, but DON’T WORRY!”

We were left with questions like, And this case works how? And which knob do I twist, again? And how long does the oxygen last? And which one is the ejection button? And will it explode in a hot car? And how many do we need to keep on hand? And will it explode on the road? And who do we call for refills? And will she die if it comes out of her nose at night? And why won’t you send us home with a pulse oximeter? I DON’T CARE IF IT BEEPS ALL NIGHT! And will it explode in the house?

“She’ll be fine.” They said. “We wouldn’t be sending her home with you if we thought she wouldn’t be.”